DEUTSCH | ROMANES

Resistance and the Evolution of a Roma Aesthetic

Guest Commentary by Daniel Baker

Reflections

The Roma aesthetic has been historically most evident within the domestic space. Within this realm, objects elicit value and admiration through their ability to fulfil multiple roles. This objective is reflected in the close attention given to the often ornate decoration of functional objects with icons and symbols that transform them into reflections of Roma life and Roma values. As such the Roma aesthetic can be seen as operating across the practices of art and of living. This observation is not meant to frame a romantic ideal, but to describe a strategy for survival rooted in practicality and innovation.

When avant-garde movements of the past admired Roma culture for its seemingly effortless creativity, shamelessly aping Roma style in a stand against convention, it was not any singular artistic activity that they sought to invoke, but a way of life suffused with creative actions, energies and resistances. Historically, art and life have been inextricably linked within Roma culture – artistic practice being far too embedded within the broader social, cultural, and political landscape to stand as a separate entity.

This co-dependence of the social and the artistic is implicit within Roma visuality – or the collective qualities embedded within objects that originate from, or circulate within Roma communities. These include artefacts made by or admired by Roma such as tools, textiles, toys, and other trappings of everyday life – and most significantly home décor. Here the family comes first and requires a closeness of attention beyond all else. Here all elements acquire intense aesthetic significance and visual interest. Here the boundaries between life and art disappear. The shared qualities found within such environments could also be described as a Roma “style” which, when extended beyond the realm of the visual to include wider sensory perception, form the foundations of a Roma aesthetic.

The innovation evident within Roma creativity reflects a pragmatism born of a history of marginalisation. Life at the edge of society has shaped Roma’s understanding of the value of adaptability and transition – contingent qualities that have continued to inform the developing Roma aesthetic to produce a set of values that are routinely played out through visual and sensory markers. The reasoning behind Roma’s focus on visual and performance strategies becomes clearer when we consider the historic absence of a literary tradition within the Roma world and its consequent implications for individual literacy. These combined historic factors continue to inform Roma’s acute visual sensibility and complex aesthetic vocabulary to position visual display as the main focus of cultural narrative – as evidenced not only within the visual arts, but also within the realms of performance including dance, song, storytelling, and oral histories.

Actions

My observations regarding Roma aesthetics stem from my interests as an artist and as a researcher. At the beginning of the 21st Century I was struck by the lack of formal analysis of Roma visual culture – a lack which seemed to echo Roma’s lack of visibility within society. This absence suggested to me a direct relationship between cultural visibility and social agency for Roma and prompted me to delve deeper.

During 2006-7 I was involved in two significant Roma visual arts projects: ‘No Gorgios’[1], for which I acted as curator, and ‘Paradise Lost’[2], for which I acted as exhibitor. The former was a community-based grass-roots representation of Romani artworks made in the UK and staged in London, and the latter a high profile production of works by Roma artists from across Europe framed within the most prestigious of contemporary art showcases, the Venice Biennale.

These two events formed what was in effect a snapshot of contemporary artistic practice by Roma. My subsequent analysis of objects from the London show formed the foundation of my doctoral research into Gypsy visuality, whilst the Venice exhibition included a number of artworks of mine developed in relation to my early research findings. The techniques, narratives, and subject matter exhibited in ‘No Gorgios’ were on the whole mirrored in ‘Paradise Lost’. These included an eclectic mix of media including photography and video as well as traditional Roma artistic activities such as painting, needlework, metal work, and carving.

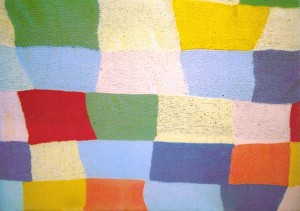

The London exhibition showed items that included painted wooden panels from a caravan interior, metallic fabric flowers, collaged representations of the holocaust, knitted blankets, wooden clothes pegs, and the customised knives used for carving them.

The paraphernalia of rural life and domesticity were frequently represented and combined to draw strong associations with nature and freedom as well as family life, community, and social injustice.

A number of the objects on display exhibited a versatility which enabled them to occupy differing realms simultaneously.

This was generally manifest in a combination of functionality and ornamentation, whereby useful object like tools or blankets were decorated with patterns and symbols to increase their potential use by transforming them into sites of artistic nourishment and sources of cultural narrative.

An exaggerated opulence was routinely evident in the functional objects on display, as conveyed through the use of rich embellishment and shiny materials which captivate and at the same time divert attention. This effect is also achieved through the juxtaposition of texture, pattern, and bright colour – eye catching effects which simultaneously fascinate and confound us.

Some objects offered the viewer more than one possible use through the suggestion of multiple functions – a mechanism of resistance that was most clearly witnessed in Simon Lee’s animal-handled catapults, which are simultaneously toys and weapons.

My research into Romani visual culture has identified some significant elements that combine to form the basis of the Roma aesthetic. To summarise these elements, core themes include Community, Family, Freedom, Gender, Home, Resistance, Tradition, and Wildlife; and key qualities include Adaptability, Captivation, Discordance, Functionality, Interruption, Ornament, Performativity, and Reflection.

Stories

The main focus of my research has been artefacts that circulate within Roma communities made by those who might not necessarily consider themselves to be artists making art. So how are the elements of the Roma aesthetic manifest within more directly recognised art activities such as the tradition of Roma painting, which has gained recognition since the late twentieth century? This rich and extensive body of work, much of which continues to evade exposure through lack of permanent exhibition space, is rightly considered an important cultural, artistic, and political document, depicting as it invariably does the direct Roma experience.

Here the preoccupations of the Roma aesthetic are depicted in narrative terms rather than experienced through direct physical contact. Themes of community and family, for example, are conveyed through visual story telling rather than experiential means. Paintings narrate the comfort and adaptability of family and community, whereas material objects like blankets and tools let us experience that comfort and adaptability through multi-sensory interaction.

Narrative pictorial accounts also perform another vital function – by generating visual histories they not only expose Roma exclusions from written histories, but also establish our own alternative record. These autobiographical gestures of resistance, as seen in the work of Kiba Lumberg and Damian and Delaine Le Bas for example, seek to make visible that which is overlooked – to reify that which is denied within the literatures on which society is founded. This hunger for pictures of our community is echoed in our fascination with the photographic image as it depicts people and landscapes that support Roma family histories and cultural narratives.

Resistance remains a recurring element across the Roma aesthetic.

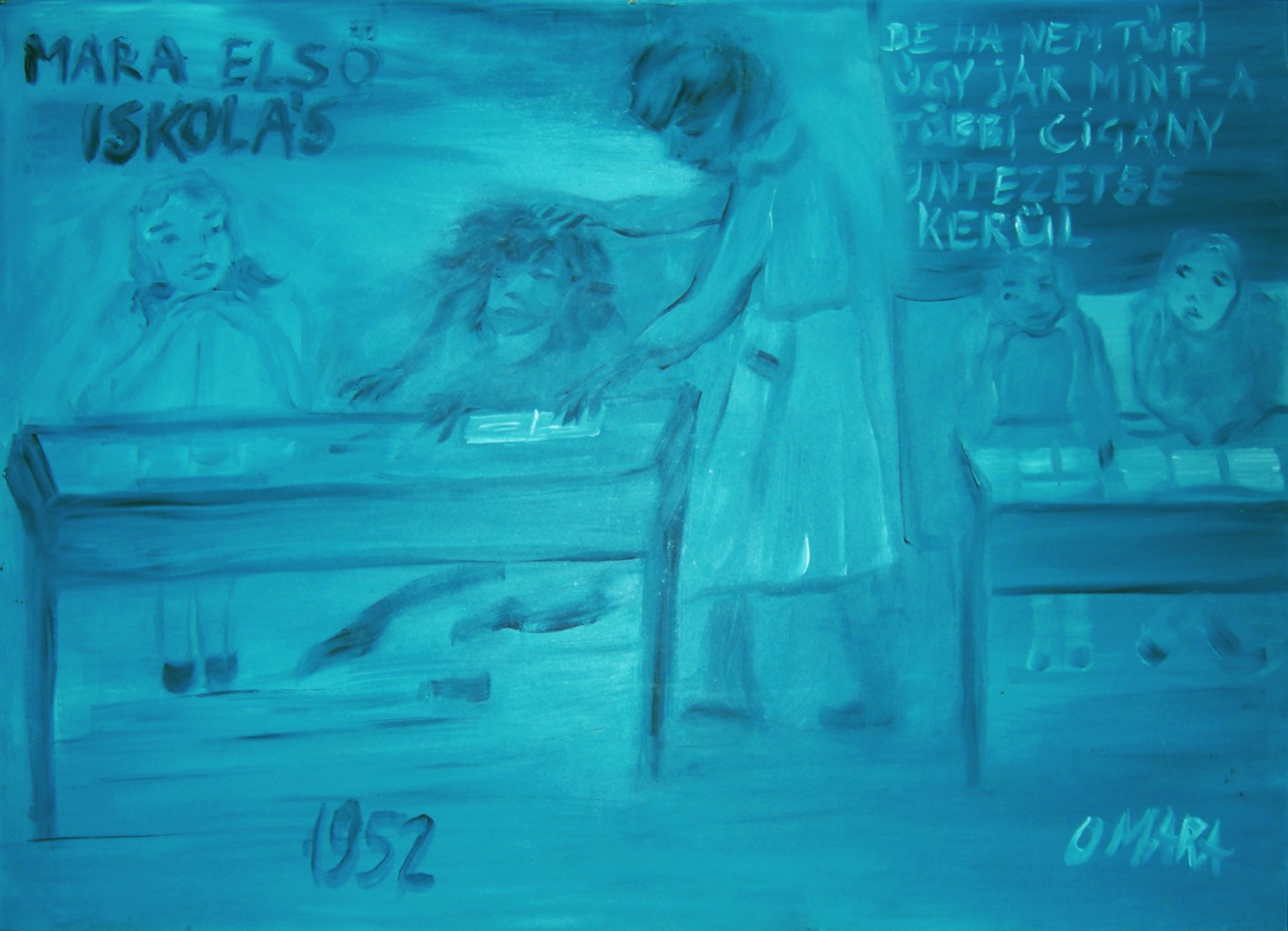

Within Roma painting this can be seen in the autobiographical works of Omara, which mark a lifelong struggle for equality for herself and her family against a tide of abusive and discriminatory establishment aggression in Hungary.

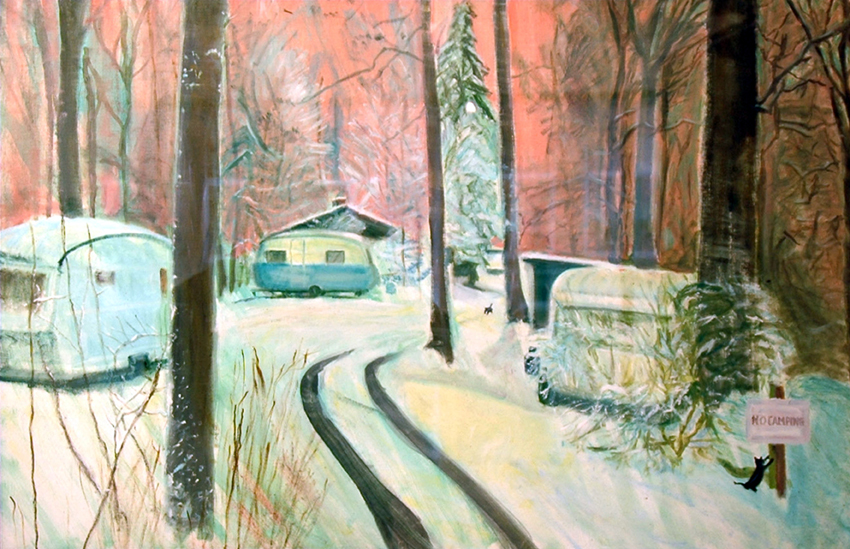

The paintings of Shamus McPhee depict families past and present along with the makeshift dwellings that some, including McPhee’s, continue to inhabit on the neglected local authority site at Bobbin Mill in Scotland.

This site was part of an assimilationist experiment carried out by the Scottish authorities from the mid-1950s which sought to quash the Scottish Gypsy Traveller community through a process of cultural denial, causing decades of struggle for the families involved. Despite obstacles both Omara and McPhee continue to draw upon their experience of life to produce art works that operate as integral to their pursuit of cultural visibility, recognition, and equality.

McPhee’s paintings were shown at the ‘No Gorgios’ exhibition alongside the amorphous knitted works of Celia Baker and the intricately sewn patchwork quilts of Trish Wilson – works that prompted the development of my ‘Blanket’ series, which explores the mechanisms of protection through juxtapositions of display and concealment.

The works of both Celia Baker and Trish Wilson combine visual and material signifiers of the Roma aesthetic to produce resistant objects which at once occupy the realms of the domestic, the communal, and the political. Here disparate material remnants are brought together to offer some kind of unification and protection amid networks of difference that join together in greater or lesser harmonies – an eloquent portrayal of the path that we as Roma continue to navigate.

1. Appendix 8, Gypsy Visuality: Gell’s Art Nexus and Its Potential for Artists, PhD thesis, Royal College of Art, 2011. ↩

2. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/paradise_20090615.pdf ↩

Daniel Baker is an artist, curator, and researcher.

A Romani Gypsy born in Kent, he holds a PhD on the subject of Roma aesthetics from the Royal College of Art, London. Baker acted as exhibitor and adviser to the first and second Roma Pavilions “Paradise Lost” and “Call the Witness” at the 52nd and 54th Venice Biennials respectively. Baker’s art and writing examine the role of art in the enactment of social agency. His work can be found in collections across Europe, America, and Asia. Baker currently lives and works in London. He is member of the respective working groups of RomArchive’s sections Dance and Visual Arts.

Visit the Website of Daniel Baker.

WHAT WOULD YOU LIKE TO READ NEXT?

Back to the BLOG

FURTHER INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT

About RomArchive

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

Press Area

Project Participants & Archive Sections

Ethical Guidelines

Collection Policy

Sponsors | Partners

Privacy Statement

Imprint | Disclaimer